|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Article by Denney Barnette - 1948 Beginnings are always interesting.

The birth of new things, be it in an animate form or just a new

idea, has certain appeal to almost everyone.

Yet the most important thing is not so much the beginning itself

as the progress made from the beginning.

Such an origin has even greater appeal when it has a personal

effect on an individual as did the birth of this plant on everyone that

is now or has ever been an employee.

Surely, there is no better way to portray the

commencement of the operation of our plant in 1925 and its progressive

development throughout the years than to relate the stories of a few of

those first employees who were here at the first and have remained to

see the passing of each milestone along the road of progress.

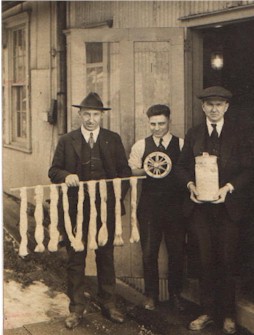

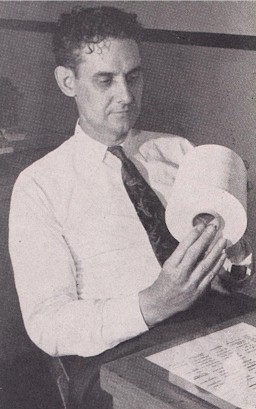

William D. “Bill” Hunt, bacteriologist in Plant

1 Chemical Laboratory, really saw the beginning of the production of

rayon at Old Hickory. Construction

of Plant 1 Spinning Room wasn’t even completed when, in answer to an

advertisement in a Nashville newspaper, Bill became a laboratory

technician here on January 22, 1925. While talking to him about the “old days” we

found Bill to be virtually a walking history book.

He frequently consulted dates jotted down inside the doors of his

storage cabinets or referred to various notations in memorandum books.

He exhibited a rent receipt dated March 21, 1925, which was for

the first rent he paid for a Company house.

This receipt is headed “Du Pont Fibersilk Company,” which was

the designation of our branch of the Company at that time.

He also has the patent agreement that he signed on May 13 1925,

and from the back of a cabinet came laboratory analysis reports of 1925,

probably some of the first records made.

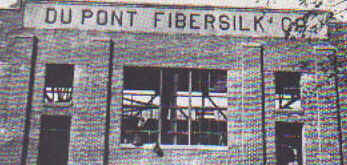

Front of plant during construction Although the walls and roof were up in Plant 1

Spinning Room, it wasn’t completely closed up and trucks hauling dirt

drove right into the Spinning Room during those first days that Bill was

here. The Laboratory was

located in the corner Plant Spinning Room just to the right of the

entrance to the stairs leading to the present Lab.

Bill used to drive his 1924 T Model right on back and park just

outside the walls of the Laboratory.

During those cold days of the winter of ’25 he would have to

make a trip to the Power House and borrow hot water to get the old Ford

running when he got ready to leave.

The area now covered by Plant 2 was practically a woods and a

corral of horses was located in this vicinity.

A filling station and restaurant was located just across the

street, where our parking area is now located.

Bill’s first days were spent unpacking equipment

and getting prepared for operation.

Construction workers were still installing lights and hot lugs.

According to him, there’s no comparison between that equipment

and the ultra-modern equipment present in the Old Hickory Laboratories

today. Most of the cabinets

and tables were “homemade” and no glass-blowing equipment or many

other items of equipment considered standard today were in evidence

then. There were four employees at the beginning and this

number was increased to only eight or ten for quite some time after

operation began. Here were

performed, in addition to the functions of the Chemical Lab, all

physical testing done in those days as well as the cleaning of

spinnerettes. Today there

are 52 people in the Chemical Laboratories alone, besides the dozens in

Physical Testing and Spinnerette Labs and the other related departments. For a short while, the Laboratory had the only

phone in the vicinity and the Lab personnel had to serve as messengers

for First Aid, located adjacent to them, and Spinning Area supervision,

whose office was next door. Bill

recalls that he helped Anne Hoskins, nurse now at Cellophane, to unpack

and set up the equipment for the original dispensary, located in a room

just about the size of one of the doctor’s offices in our present

Medical Department. There

were a couple of cots and a nurse on duty with necessary supplies to

apply emergency treatment to injuries.

This small first aid station was a far cry from our modern,

well-equipped Medical Department, complete with X ray and staffed with

four doctors and a corps of nurses. Mr. Hunt well remembers the beginning of operation.

He says he saw a sample bottle of the first viscose produced by

Plant 1 Chemical Building. To

him it looked like a bottle of sorghum molasses.

He also ran the control analysis on the start-up caustic and

bath. The first rayon yarn

produced reminded him of binder twine. “In those days I never heard quality

mentioned,” says Bill. And

even though his duties are now not so closely related to the actual

manufacture of rayon, Bill admits he is just naturally curious and

therefore likes to keep up with what is going on.

Consequently, he’s well aware of the tremendous improvement

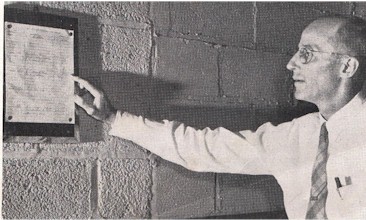

that has been made in production methods and quality of product. When you mention safety, you touch on a subject

that immediately sparks a note of interest in the face of Mr. Hunt.

To compute his own days without an injury just subtract his

service date from the present date and you’ll have it, over 23 without

a blemish on his safety record. Being

a member of the 8000 Day Club himself, Bill is interested in the records

of his fellow employees and so it’s an additional duty of his to

maintain the records for his area on days gone without an injury.

The outstanding records of these people who work in an area where

hazards are many are a good example of progress from the standpoint of

safety. Even though it was

two or three years after he went to work here before Bill Hunt attended

a safety meeting on this plant, things have definitely changed.

Now Plant 1 Chemical Laboratory has a safety meeting every Monday

morning and has a combined Control Section meeting every five weeks.

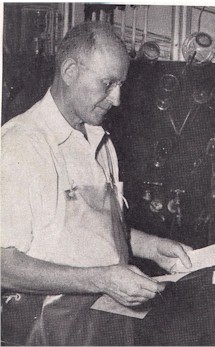

Bill’s present job is very different from any

other on the plant. It

consists of running bacteriological tests on all water used in this

plant, at the Cellophane Plant and in the Village, as well as similar

tests on milk, trade waste and sewage. You don’t have to talk to him long until you’ll

be convinced that Bill Hunt is “sold on his job.”

He says he fully intended to make a career of his affiliation

with DuPont when he answered that ad in 1925.

He seems to be doing just that and enjoying every minute of it. Russell Shedden, now Plant 1 Textile Area clerk,

working in the Production Control Section , cast his lot with DuPont in

Old Hickory on February 26, 1925. Russ

has the distinction of having worked in two departments which are no

longer in existence on this plant:

the Wash and Bleach Area, discontinued in 1939, and the Sales

Office, which was moved to Chattanooga in 1930.

His reasons for seeking employment with Du Pont

were two-fold. He had just

talked a young lady into becoming Mrs. Shedden and was interested in

securing a job with a future in this locality.

Also he had formerly had a job on the road for Marshal-Field of

Chicago and had an idea of learning about rayon with the intention of

some day getting into the selling end of the business. Thus it was that he came to be on of the first men

hired in the Wash and Bleach Area, almost before construction was

completed. The walls in the

front of the buildings were not completed.

Men were still working on the sawtooth roof and completing the

insulation. Those first few

days were spent cleaning up after construction and washing waste.

Naturally with operation in its infancy, a large percentage of

that first rayon produced for several weeks went into waste.

Russ recalls that at one time there must have been over a hundred

thousand pounds of waste on hand. This

was washed in huge mastic tubs with a large fire hose. So many of the present-day employees have no idea

as to what the Wash and Bleach Area was like, we will attempt to

summarize the operation of the department that Russ helped to start some

23 years ago. Where

desulphuring now takes place while the rayon is in cake form, in those

days the Wash and Bleach did this job to the skeins after they left the

Reeling Room, the cakes receiving only a preliminary acid wash in the

Spinning Room. All the

first year’s production went to skeins. The four machines that went into operation in Plant

1 to accomplish this wash and bleach job were long, tunnel-like enclosed

racks with the washing solutions and bleaching solutions (primarily

chlorine) entering through the top.

The skeins were put on rods at the front of the machine and

charged into the machine. The

first step was a hot wash of caustic, next a cold wash to remove the

caustic, then the bleaching solution was applied.

This bleach was washed out, a second bleach given and washed out,

then the rayon passed into the finishing stage.

The skeins were then removed still wet and after being wrapped in

large muslin cloths were put into a centrifugal wringer to remove excess

moisture. The skeins were

the restrung into a dryer. In this dryer, which somewhat resembled those

dryers now being used to dry the rayon in cake form, the first step was

the removal of the moisture with heat until the rayon was almost dry.

It was then cooled and humidified or a certain amount of the

moisture reinstated before being removed to a rolling rack, or “Trojan

horse,” to go into Skein Inspection.

This operation normally required for operators, one to charge the

skeins into the washer, one to remove and centrifuge the wet skeins, a

man to charge the dryer and another to transfer the rayon from the dryer

onto the “Trojan horses.” The

amount of handling necessary for this method was the primary objection

to it. The delicate nature

of skeins of rayon, especially when wet, created an eternal problem of

injury to the yarn through handling.

Mr. Shedden, during a lull in Wash and Bleach

operations, assisted a representative of the Universal Winding Machine

company in leveling and installing the first winding machine in the Old

Hickory Plant, early in 1926. Later,

after progressing to the position of supervisor in the Wash and Bleach

Area, Russ went into the Sales Office where he eventually became chief

clerk. This Sales Office,

located approximately where the Purchasing Office is now, took orders

for rayon by phone and mail, having no teletype at the time.

They also received customer complaints.

Upon the transfer of this office to Chattanooga, Russ went into

the Production Control Section, which took over some of the duties of

the Sales Office. In the type work in which Mr. Shedden has been

engaged, he has been engaged, he has been in a good position to note the

great advancement made in the quality of the product produced here.

He can remember when poundage, not quality, was the keynote.

However, since his main job now is compiling weekly and monthly

reports on rejects and grading, it is evident to him that progress in

the field of quality has been outstanding.

When asked what he considers to be some of the major

contributions to this notable change, Russ listed: minimizing the

handling of rayon; use of information gained from customers as to what

is required; and foremost, the increased number of quality-minded

employees who have come to realize that quality of product is one of the

prime constituents of job security. Also, as is ever long-service employee, Mr. Shedden

is greatly impressed with the progress made in the field of safety.

From the days prior to 1930, when there was virtually no

organization for safety, activity has been increased until today the

doctrine of safety has been instilled in each and every employee.

Personnel have become so safety minded that they have carried

accident prevention home with them and educated everyone with whom they

have come in contact. With 23 years of recollection behind him, in which

he has seen the plant “come a long way,” Russell Shedden is

convinced that the next quarter of a century will bring changes just as

revolutionary and progress just as definite.

None should be better informed about the early-day

activities than W.T. “Tom” Jackson, now Day Crew foreman in Plant 1

Spinning Room. Mr. Jackson,

who began his career with Du pont on November 30, 1924, as a rigger on

Construction, helped to set the first boilers and generators in the

Power House. This

association with the Du Pont influenced him to the extent that he

decided he would like to transfer into Operations and continue as a Du

Ponter. This transfer was

accomplished and he began his career in Plant 1 Spinning Area as a pump

tester on April 15, 1925. At that time only four of the old Type 3 spinning

machines were in operation. In

his capacity as pump tester it was Tom’s responsibility to regulate

the denier by controlling the flow of viscose through the pumps into the

acid bath. The only denier

run for the first two or three years, according to Mr. Jackson, was

150-24. As a comparison

today, there are 15 different deniers being spun in Plant 1 Spinning

alone, ranging up to 900 denier. In

1925, a denier change necessitated a pump adjustment on each individual

pump with a pair of pliers and a wrench.

Today, the PIV control, a mechanical chain drive on the end of

the machine, makes the adjustment on the entire pump delivery of the

spinning machine at one time. While many of us may not be too familiar with

present-day spinning machines or their operations, we can certainly

visualize the improvements made after getting a description of those

first four machines compared with the 231 we have operating in both

plants today. These machines which pioneered operation at Old

Hickory were built on a platform as the machines now located in Plants

1B and 2A. But this was

before the days of Desulphuring Area and the wash racks were built

between the machines right on the platform.

The cakes of rayon were removed from the spinning machines and

immediately hung on these racks for the preliminary wash.

These machines had no “goof trough” (trough to catch viscose

dripping from the pumps) or sewers through which to run this viscose.

They used long metal pans about four feet long under the pumps.

It was necessary to frequently empty these pans into garbage cans

to be carried out. On those first machines, one side (50 buckets) was

driven by a single motor. Thus,

if I became necessary to stop one bucket, one entire side of the machine

ceased operation. Therefore,

the doffing (removing of completed cakes of rayon from the bucket of the

spinning machine) required that the machines be shut down completely and

then threaded back up. It

required 30 to 45 minutes for this operation.

Today, each individual bucket is driven by a separate motor and

so one position may be stopped at a time.

It now takes a crew approximately six minutes to doff an entire

machine and even then each position is spinning “feed wheel wraps”

while the bucket is stopped. These

are sold as a by-product, so actually no production time is lost. Instead of roller type guides in the bath trough, a

porcelain-tipped hook guide was used.

This type guide caused many broken filaments.

Therefore, their elimination was a major contribution to the

improvement of quality. The

rayon thread, after leaving the bath trough, simply went over the feed

wheel and made no loop, going directly into the funnel.

The speed of these wheels on those first four machines was 129

revolutions per minute. Today,

the RPM of our machines runs as high as 250.

This results in more poundage and, strange to say, better

quality. According to Tom, it’s a toss-up as to the

greatest problem encountered in early-day spinning, between breaking

funnels and flying buckets. These

funnels through which the thread passes down into the bucket (which

spins the rayon into cake form) were made of glass in those days instead

of hard rubber as they are today. Naturally

they were easily broken and were a continual problem not only because of

the expense involved but as a perpetual safety hazard. It hasn’t been so long ago when this country went

through the “flying saucer” era.

All this might have brought back some memories of those flying

buckets for many employees who used to work in the Spinning Room in the

“good ole days.” Buckets

of the present-day spinning machines are in a lock-type compartment and

can’t come off during the spinning operation, but before these

compartments, with their wooden covers and safety rails, were installed,

it was not an uncommon sight to have a bucket go sailing over a machine

and break down several positions on the next machine or to have a bucket

go dancing down the aisle between the machines spinning like a whirling

dervish. In addition to the afore-mentioned steps of

progress, Mr. Jackson also mentioned improvements in the elimination of

fumes due to change from wooden fume ducts over the machines to ducts

under the machines and the great improvement in the viscose (from which

rayon is spun) through continual research and development. In summing it all up, Mr. Jackson said,

“there’s just no comparison between the production of rayon today

and in 1925. Looking back,

I can’t see how they possibly sold the stuff we made then.” There is no trace of nostalgic longing for the

“good ole days’ in the face of Annie Jo Elam when she reminisces

about her early days at the plant.

As she expresses it, “When you look back to the first year of

operation, it is almost inconceivable that there has been so much

progress made.”

Mrs. Elam, whose adjusted service date is May 26,

1925, fist came to work on April 9 of that year as a reel operator.

She had just begun working and her first job had been on the

night shift in a bakery. She

came to Old Hickory because she wanted a day job.

Like so many of the wearers of the three star oval, she had no

intention of staying very long. “She

was just kinda looking around.” Even

after six months she took a vacation and shopped around for another job.

But up to now she says “I’ve never found anything that would

beat what I had.” When Annie Jo first entered Plant 1 Textile Area on

that day in April 1925, it contained two sections of reels.

She recalls that the thing that impressed her most that first day

was the noise of the clicking flys. A recollection of her training period brought to

her mind one of the things in which much progress has been made.

Instead of going into a training class in a training room, as ins

the case with new Textile Area operators now, Mrs. Elam was put in the

area on the job and was instructed only until it was felt by her

instructress that she was capable of accepting an assignment.

On a new job, in the noise and confusion of a new environment and

a little nervous, she naturally could not adapt herself so easily to her

new duties. In those days, a reel operator’s assignment

consisted of one fly, or eight girls to each reeling machine.

All lacing was done by hand, the operator lacing one fly while

another filled. Thirty to

forty “doles” (skeins from one filled fly twisted together) was top

production. In comparison

today, with innumerable improvements in machinery and methods plus the

skill of better trained operators, one operator can carry an assignment

of as many as eleven flys on the light deniers and 127 “doles” per

day on the heavier deniers are easily obtainable. Of course, the major innovation to reeling was the

introduction of automatic lacers. At

first rumors of such machines, Mrs. Elam said that the consensus of the

reel operators was that “such talk was crazy.”

However, it proved to be true and today these mechanical fingers

can lace as many as 435 doles per day with two operators on the machine. Many were the problems of reeling in those days.

Flying sulphur from the cakes covered the machines in a short

time and frequent thorough clean-ups were necessary.

Cakes came from the Spinning Room on aluminum inserts without a

wrapping of any kind. This

absence of a protective covering certainly

did not decrease the defects from handling.

Colored bands on the inserts identified deniers instead of the

design on the wrap as today. Power

shutdowns were frequent. Many

times an early morning shutdown would necessitate the operators’ going

home for the rest of the day. Of course there was little emphasis on quality in

these days. The primary

objective was production. Everything

and everyone was new, so the main thing was to learn to produce rayon.

Up until the fall of 1925, the operator’s waste wasn’t even

checked. Therefore, it was

not an uncommon practice, if a cake didn’t run so well, to discard it

into waste and try another. Mrs.

Elam recalls one instance of finding a grasshopper in the middle of a

cake she was reeling. Her

first recollection of any forward steps in quality was in 1926, when an

inspection for rust or “red spots” was started. There must have been little or no safety education

or publicity in those early days because if there was it couldn’t have

been very extensive, as Mrs. Elam doesn’t remember it.

Housekeeping consisted merely of keeping your work area clear

enough to enable you to move about. Most work weeks were six days and 57 hours, 10

hours a day Monday through Friday and seven hours a day on Saturday.

Many operators would come to work early in order to have extra

production before work time. Mrs. Elam says she doesn’t remember much about

the rest of the plant in 1925 because in those days, before RAYON YARNS

and other means of disseminating information, employees knew very little

about what went on outside of their own department.

She does remember, however, the first cafeteria in a corner of

what is now Plant 1 Shipping Room and how employees ate their lunches on

the shipping platform. Mrs. Elam worked in the Reeling Rooms as an

operator, on reinspection and as forelady until her transfer into the

Physical Testing Laboratory in 1930.

Today she has a most interesting job in the Cross Section

Laboratory and after 23 year as a DuPonter is very much impressed with

the great progress that has been made in production methods, quality,

safety and housekeeping. She

and her husband, Herbert Elam, a supervisor in Maintenance, form one of

the many husband and wife teams that have contributed to this progress

that has been made since that embryonic period of 1925.

While Claude Coleman many not have been one of the

first individuals to go to work in Plant 1 Textile Area, he surely has

been in that area longer than anyone here today.

Even though he quit a couple of times to go to school, he has

been around Plant 1 Textile off and on for over 22 years and has worked

on practically every job in the area.

From that first day, March 2, 1926, until the present he has been

a service operator, pickup operator, winderoperator and foremand and at

present is a shift supervisor. He

had just returned from that now historic “Florida Boom” and learned

about Du Pont from a girl who had come from his home tome, Livingston,

Tennessee, to work at Old Hickory.

Claude says he well remembers that first shift he worked here.

He came to work in the afternoon and worked 14 hours putting

colored denier bands on the old aluminum inserts. On that day in 1926, there were only approximately

200 winding machines in Plant 1 Textile Area, the rest of the room being

filled with reels. Today

there are 685 winding machines in Plant 1, plus 576 in Plant 2B.

When asked for a comparison between those winders of then and

now, Claude replied, “Gosh, they’ve been practically made over.” In the early days, there was a frame under each

machine filled with sawdust like the floors of a frontier saloon.

There were sawdust bins in the corners of the room from which

these frames were refilled at intervals.

Present-day machines have improved spindles and guides and

different tension and the speed of the spindle has been increased from

1000 RPM to 1350 and even as high as 2000 on tube winding.

Then each winding machine had an individual intermittent oiling

unit which was driven by a belt. These

belts’ breaking and jumping off were a continual nuisance.

In addition this type oiler sprayed oil like “Old Faithful”

and after a shift, the legs of the operator’s trousers were spotted

with oil up to the knees. At

present, the oilers that put the proper amount of oil into the yarn

travel at a greatly reduced speed and 96 spindles, or one entire side of

a winder alley, are tied together and propelled by a single chain-driven

shaft from one motor. In 1926, the machines were grouped into 24-spindle alleys instead of 96 as in a present-day alley. Over these machines were stock racks with four red poles and four white ones. A rayon distributor or “stock boy” put cakes of rayon on the white poles. An inspector or “thread marker,” as they were called, came along and checked the cakes. Those considered in condition to run were placed on the red rack, from which the winder operator got his cakes for winding. Today the same operator removes the rayon from the carriers, inspects it and winds it. The elimination of rayon hanging over the machines and only one person handling the cakes are decided improvements in housekeeping and quality. Other equipment improvements recalled by Claude

were improved pin trays on which to place finished cones and the buggies

on which these trays are placed. The

old type buggies plus the soft asphalt-covered floor that they had to

move over in 1926 made moving a loaded buggy a two-man job and at times

it was like “pushing a log wagon out of a mud hole.”

The scissors used by winder operators in the early days of

operation were of the dime store variety like baby sister uses to cut

out paper dolls. Today they

are specially designed and round for 1/8” and ¼” knots. Improvements in methods have been so great that it

ispossible for operators to run more production with much less effort.

According to Claude, an operator who could run 36 spindles would

have really been a “whiz” in those days.

Now operators carry an assignment of 124 spindles on an average

denier. In those days

everything was wound into two-pound cones on a 12E spindle on a cone

core that much resembled an ice cream cone, coming to a sharp point at

one end. Now production is

put out in two-, three-, and four-pound cones on three-degree cores.

It woul dhave been a miracle in 1926 to have equaled the

approximately 55,000 pounds of production per day that is presently

being wound in Plant 1 Textile even with the same number of machines

that there are today. The

primary problem was summed up by Mr. Coleman as being “just getting

the stuff to run.” The

top grade rayon then was not as good as the present day SR-3 (lowest

grade rayon). The cakes

were thin and filaments easily broken.

“We’ve come such a long way that there’s no comparison

between present-day quality and the poor excuse for rayon produced in

1926.” Claude couldn’t complete his recollections of the past without touching on the forward steps in the field of safety. He believes that simple education of the operators through personal contact has been the biggest factor in the reduction of the accident frequency rates. In those early days of operation the turnover of personnel was so rapid that an educational program was practically impossible. People were here today and gone tomorrow. This in itself is a big contrast between the past and the present, when a large percentage of the employees who come to work at Old Hickory come with the intention of making their job here their career, as has Claude Coleman.

Rayon Plant I - Today - Near Reemay®

|

|